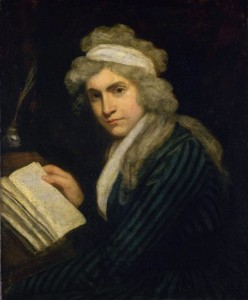

This month’s Kickass Woman is Mary Wollstonecraft. I am sad to say that Mary Wollstonecraft never, to my knowledge, literally kicked anyone in or on the ass, although I’m happily writing fanfic in my head in which Wollstonecraft spends her days beating up her oppressors with Regency English Kung Fu. In real life, Mary was a kickass woman in the sense that she insisted on living her life on her own terms, she was a foreign correspondent in France during the Reign of Terror, and she wrote powerful books and essays that shaped feminist thought for the next two hundred years. Today, she is arguably most famous for having given birth to Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein ( A | BN | K | G | AB | Au | Scribd ), but during Mary Shelley’s life, Mary Shelley was known as the kid of Mary W., and Mary Shelley was put under a lot of pressure to live up to her famous and infamous mom.

We romance readers love to fantasize about the Georgian and Regency time periods, but in real life they were incredibly difficult time periods for people of little means and for women. Mary Wollstonecraft’s story includes trigger warnings for rape, domestic violence, abandonment, alcoholism, slut shaming, death in childbirth, and lots of dead babies and dead people in general. Believe me when I say that while I love wearing my Regency dresses and reading my romances, the actual time period was not a happy time for a woman to live in, unless you were a woman with a lot of money and a lot of luck. Mary Wollstonecraft had neither.

Mary was born to a severely alcoholic, abusive father. She spent her nights listening to her mother being raped in the next room and because her mother was always injured, sick, pregnant, recovering from giving birth, or all of the above at once, Mary spent her days raising her six siblings. In her later life, she had a particularly important, and often contentious, role in the lives of her sisters Everlina and Eliza. Mary helped Eliza escape from an abusive husband, but Eliza had to leave her baby behind and the baby died soon after. Mary’s brothers were able to find various positions that kept them independent, but sisters Eliza and Everlina remained at least partially dependent on Mary during her entire life.

Mary’s first jobs were as a lady’s companion and as a governess. She hated the work and she hated the people she worked for, but she did become attached to the daughters she was governess to. One of these daughters took Mary’s freethinking attitudes so very much to heart that she ended up running away with a married cousin, who was then killed by her brother (DRAMA).

Mary also founded a boarding school for girls. She had high goals of educating young women to be independent and equal with new educational approaches, but she ran into roadblocks. One was that she enlisted the help of her sisters, and they hated it. They worked hard, for barely any pay, and they did not share Mary’s passion for the cause or her talent for teaching.

The other roadblock was that Mary developed what was at the time commonly referred to as a “passionate friendship” with a woman, Fanny Blood. She and Fanny ran the school together, but Fanny suffered from consumption. Desperate to save Fanny’s life, Mary encouraged Fanny to marry a man who lived in sunny Portugal. Fanny married him but died shortly after giving birth to a baby who also died. Mary was so heartbroken from this loss that she told people that she hoped she would die soon, as well. Her absence from the school (she rushed to Fanny’s side when she realized how sick Fanny was) combined with the lack of enthusiasm from her sisters was enough to end the school project. However, so many members of her family were dependent on her that Mary had to find another way to earn a living, and she settled on writing.

Fanny was important to Mary not only because of their relationship (which, while it may or may not have been physical, was clearly deeply intense) but because of Mary’s relationship to Fanny’s family. Through her friendships with Fanny Blood, plus an earlier friend, Jane Arden, and a local family (the Clares) Mary was given opportunities to educate herself through reading. She was exposed to works of political philosophy, including the writings of John Locke. This was a period of time during which a lot of people were discussing the rights of men. Mary was one of the few who was talking about the rights of women.

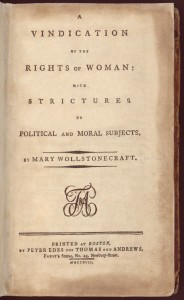

After her school closed, Mary became determined to live by her pen. At first she wrote anonymously. She made her first really big splash in 1790, with A Vindication of the Rights of Men. In this book, Mary attacked the idea of a system based on hereditary status and female passivity in favor of a meritocracy. The first edition, published anonymously, was well-received, but when the second edition came out with her name on it reviews were much more condescending and dismissive. When she “came out” as a woman she was savaged in the press not only for her Vindication but also for her book reviews, because she reviewed material that traditionally fell under men’s purview.

Her most famous work was (and still is) A Vindication of the Rights of Women, written in  1792. She wrote two versions – one in a hurry, the other after she had time to make revisions. Her focus in Vindication was on the importance of educating women. She was following this up with a novel, Maria, or The Wrongs of Women, but she died before it was finished. This novel is generally thought of as a more radical book, and more feminist in the modern sense of the word.

1792. She wrote two versions – one in a hurry, the other after she had time to make revisions. Her focus in Vindication was on the importance of educating women. She was following this up with a novel, Maria, or The Wrongs of Women, but she died before it was finished. This novel is generally thought of as a more radical book, and more feminist in the modern sense of the word.

Mary also worked as a foreign correspondent in France from 1792 until 1795. During this time, she met several kickass women, including author Helen Marie Williams, Madame de Stael, and the very radical author Olympe de Gouges. She also met the cross-dressing radical Theroigne de Mericourt, who will doubtless be the topic of a future Kickass Women column (Google her, you won’t be sorry). Mary faced serious peril, as the English were seen as enemies of the revolution. Several of Mary’s friends were guillotined or imprisoned. Mary was deeply distressed by the Reign of Terror, but, unlike some of her contemporaries, she did not become more conservative with regard to the original ideals of the French Revolution.

While in France, Mary fell in love with Gilbert Imlay. Both Mary and Gilbert believed, with considerable justification and personal experience, that legal marriage was disastrous for women because of the lack of legal protections that married women had. When Mary became pregnant, she was thrilled, and she and Imlay were quite proud not to be married although she referred to herself as Mrs. Imlay (this gave her more protection during the Revolution and also protected the baby (named Fanny) from being thought of as illegitimate).

However, when Gilbert decided to move on to another woman, Mary, to use a technical phrase, lost her shit. All her life she suffered from periods of profound depression, and she seems to have suffered from severe postpartum depression, not to mention being in imminent peril in a hostile country with a newborn infant. The next several two years were incredibly painful for Mary. Gilbert said he would support her and the baby, but she felt that to take his financial support without love would be akin to prostitution. She demanded, at a minimum, that he be an active, involved, present father and that he provide Wollstonecraft with friendship if not romantic love. She tried to commit suicide twice. She also travelled with her baby and a female servant named Marguerite through Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, and wrote a book that was part political essay, part travelogue, and part memoir. Marguerite’s last name is unknown, but she seems to have been considerably kickass in her own right, navigating months of arduous overseas travel while caring for a baby and keeping Mary stable enough to travel and write.

Mary first met William Godwin at a party in England when she was a young woman (pre-Gilbert). The meeting did not go well. William, who was a deeply reserved intellectual, felt that she talked too much – he saw her as a show off. She saw him as impossibly stuffy. However, when they met again, after Mary returned from her trip through Northern Europe, they had a very sweet, if challenging, second-chance romance. Both of them continued to believe that marriage was oppressive to women, but when Mary became pregnant (with Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley), they decided to marry legally to protect the baby from being called illegitimate. It was a no-win scenario, since this exposed Mary’s baby by Gilbert, Fanny, as illegitimate. They set up separate but adjacent households and determined (with only partial success) to support each other’s writing careers. Their marriage ended tragically, however, when Mary died a very gory and painful death of childbed fever about one week after giving birth to Mary Shelley.

After Mary died, William wrote a biography of her that exposed her love affairs and her desperation to win Imlay back following his desertion. Mary was always a controversial writer, and these revelations allowed critics to write her off as a deranged, love-starved woman, someone akin to a prostitute, and someone who could serve only as a cautionary tale for other women. A Vindication of the Right of Women was quite well received when it came out, but after William exposed her problems with her love life, her work became seen as the rantings of a self-destructive hysteric. It wasn’t until Virginia Woolf defended her in 1932 that she began to emerge from the shadows as a true pioneer.

My source for this column is Charlotte Gordon’s excellent biography: Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and her Daughter Mary Shelley. In her conclusion, Gordon says:

Without knowing the history of the era, the difficulties Wollstonecraft and Shelley faced are largely invisible, their bravery incomprehensible. Both women were what Wollstonecraft termed “outlaws.” Not only did they write world-changing books, they broke from the strictures that governed women’s conduct, not once but time and again, profoundly challenging the moral code of the day. Their refusal to bow down, to subside and surrender, to be quiet and subservient, to apologize and hide, makes their lives as memorable as the words they left behind. They asserted their right to determine their own destinies, starting a revolution that has yet to end.

Thanks for this fabulous write-up!

I think it bears noting that Godwin didn’t *mean* to cause a scandal when he wrote Wollstonecraft’s biography; he honestly thought that if he explained her philosophy and her history and her reasons for making the choices she did to the public, they’d be just as impressed and moved by her as he was, and respect her more for it. I always feel pretty bad for him that it didn’t work out that way.

Yes, Godwin didn’t write think that one through! Godwin (in the romantic Outlaws biography) comes across as someone who was very shy and had a hard time understanding other people – he was rarely malicious but his perpetual cluelessness caused his family all kinds of problems. He seems to have had good intentions and no social savvy to back them up with.

Excellent post! I rec’d a Mary Wollstonecraft bio by Lyndall Gordon for Christmas (haven’t read it yet) and now I also want to get Romantic Outlaws.

When I hear folks remark that fictional historic female characters have “too modern a view” on equality or rights, I point to Mary W, Nellie Bly, and others. The word “feminist” might not have been around or in popular use, but the ideals surely were.

A really excellent book, based on her life, is Requiem for the Author of Frankenstein by Molly Dwyer.

[…] Smart Bitches Trash Books tells us all about Mary Wollstonecraft. […]

Kirstyn McDermott has written a wonderful story featuring Mary in the anthology Cranky Ladies of History – I can’t help but think she may have used some of the same source material!

“The Daughter of Earth and Water” is a wonderful biography of Wollstonecraft’s daughter, Mary Shelley. It touches upon how Wollstonecraft’s work influences her daughter.

Now that I am back from the hospital and have the time, I would like to mention how much of my life is made possible by Mary Wollstonecraft. She wrote and supported women’s right to think and exist at a time when this was not encouraged. Her writings encouraged many later women (and men) who worked for greater autonomy for women. Initially much of my knowledge of her was sideways – mentions of her when I read about her daughter or mentions of her by other women writers. Taking the time to learn about her as her own person was very useful to me at a certain time in my life. I am happy to see the Bitches celebrating her.

Both “Vindication of the Rights of Woman” and “Maria” are really must-reads for everyone. “Maria” really exposes just how disasterously wrong things could go for you if you married the wrong man in that era. Or were born into the wrong family.

We may think that some of the plots we read in contemporary novels are outrageous, but here’s someone who lived in the era who has written something perhaps more dramatic than we’re used to.

Here’s a link to “Maria”, at Gutenberg.

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/134

There was a novel back in the ’90s called Vindication, by Frances Sherwood, which was a fictionalized account of Wollstonecraft’s life. I remember really enjoying in, though it was admittedly harrowing.

One of the first essays I ever wrote in college was on Mary Wollstonecraft. I was used to coasting through such assignments with glory and praise, but my hard-assed writing teacher handed it back to me with the note “If you can’t spell her name, I can’t read your paper.”

I think I cried over that, in class. But I never again was so lazy. And I never did stop calling her Ms. Bohrer, no matter how often she asked me to call her Susan. She developed me as a writer and editor, and without her, I’d never have ended up in publishing, and perhaps wouldn’t have begun writing, either.

This is only tangentially related, but I found this a fascinating analysis of Frankenstein, written by Mary Wollsontecraft’s daughter. It persuasively makes the argument that the monster in Frankenstein was supposed to represent the illegitimate Fanny.

http://historybuff.com/victor-frankensteins-director-called-mary-shelleys-novel-boring-YW4rqlyzdl83

[…] and female scientists. This feature fell by the wayside when I started writing Kickass Women for Smart Bitches Trashy Books. Guest writer Max Fabin is bringing the Heroes back with his contribution about scientist Vera […]