TW: Assault, racism, sexual assault, murder.

It’s a busy season, but let’s all take a minute to celebrate Daisy Bates, the kickass leader of the Little Rock Nine and a lifelong activist. We must also celebrate the Little Rock Nine, a group of kickass students who desegregated Little Rock Central High School in 1957.

Daisy was born in 1914. When she was three, her mother was raped and murdered by three White men. As she grew up and learned more details about the crime, she became suffused with rage. A turning point for her came when her adoptive father told her:

You’re filled with hatred. Hate can destroy you, Daisy. Don’t hate white people just because they’re white. If you hate, make it count for something. Hate the humiliations we are living under in the South. Hate the discrimination that eats away at the South. Hate the discrimination that eats away at the soul of every black man and woman. Hate the insults hurled at us by white scum—and then try to do something about it, or your hate won’t spell a thing.

Daisy married L.C. Bates and the couple started a newspaper, The Arkansas Weekly, which focused on Civil Rights news. They were a team that worked together to produce and distribute the paper. They also served with the Arkansas National Association for Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

Daisy married L.C. Bates and the couple started a newspaper, The Arkansas Weekly, which focused on Civil Rights news. They were a team that worked together to produce and distribute the paper. They also served with the Arkansas National Association for Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

Daisy, then president of the NAACP, became the leader and coordinator of the effort to desegregate Arkansas schools, starting with Little Rock Central High School. In 1954 the Supreme Court had ruled that segregating schools was unconstitutional. Daisy wanted to force Arkansas to comply with that ruling. This meant recruiting African-American students to attempt to enroll in and attend classes in an Arkansas High School.

Daisy recruited nine students, ages 14 – 17, who would forever after be known as The Little Rock Nine. She had to convince their parents to allow their children to risk their lives, their health, and their sanity b y being the first African-American students to enter a high school in Arkansas.

Daisy was beautiful and a little bit glamorous, she was a good listener and a persuasive speaker, she was ferociously committed to her cause, and she genuinely liked children and young people. Her warmth and her promise to support the students with every aspect of their experience helped reassure parents.

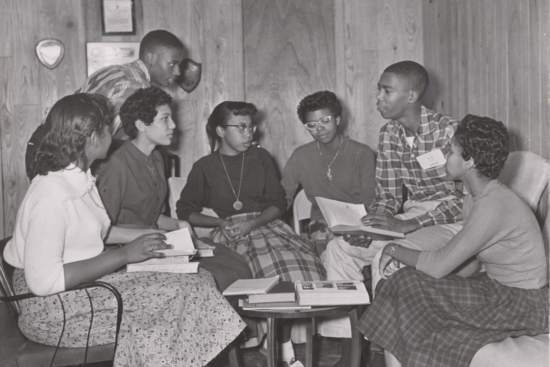

Once it was time for the students to attend school, Daisy committed herself to giving them physical and emotional support and doing all she could to ensure their safety. She escorted the kids to school, joined the PTA, and helped the students with their homework. Her home was a meeting place for the students and for fellow activists.

Daisy and the Little Rock Nine, as well as their families, literally put their lives on the line in their efforts to desegregate schools in Arkansas as well as in the rest of the U.S. They faced bomb threats and death threats. Daisy’s house was damaged. One of the students’ houses was bombed. The students were bullied physically and verbally in and out of school. Many of their parents lost jobs. All of them – Daisy and fellow activists, the students, and their families – were persistent, nonviolent, dedicated, and heroic.

After the Little Rock crisis, Daisy went on to have a career of activism in fighting poverty. She also wrote a memoir, The Long Shadow of Little Rock, which won an American Book Award.

Daisy died in 1999 and became the first African-American to lie in state in the Arkansas Capitol.

Here are the names of the Little Rock Nine and a just a little bit of what they did after graduation:

- Melba Pattillo Beals became a journalist. She taught journalism at the Dominican University of California and is the author of four books: Warriors Don’t Cry, White is a State of Mind, March Forward Girl, and I Will Not Fear.

- Minnijean Brown-Trickey was expelled from Little Rock Central High School as the direct result of White students who tormented her. She finished high school in New York and after getting a Master’s Degree in Social Work she worked for the Clinton Administration as the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Workforce Diversity. She was also a public speaker and has six children. She is the subject of Journey to Little Rock: The Untold Story of Minnijean Brown Trickey, a documentary.

- Elizabeth Eckford is the iconic subject of a photo by Will Counts that became famous and helped garner support for the plight of the nine students. Elizabeth suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder from her experiences in Little Rock and grief over the loss of her son, who was killed by police. She is the co-author of the book The Worst First Day: Bullied While Desegregating Little Rock Central High.

- Ernest Green was the first African-American to graduate from Little Rock Central High School. He held cabinet positions under the Carter and Clinton administrations. He continued to be a civil rights activist through college and later worked in finance.

- Gloria Ray Karlmark built a trailblazing career in IBM as a systems analyst and patent attorney. She has also worked on projects for Boeing, Donnell-Douglas, and NASA. She has lived in Sweden and The Netherlands since 1970.

- Carlotta Walls LaNier is a real estate broker and community activist who has worked with organizations such as NAACP and the Colorado AIDS project. She is the author of A Mighty Long Way: My Journey to Justice at Little Rock Central High School. She has also served as the president of The Little Rock Nine Foundation.

- Jefferson Thomas served in Vietnam. He also narrated the documentary Nine From Little Rock. He was a civil servant, volunteer, and speaker until his death of cancer at the age of 67.

- Thelma Mothershed-Wair earned multiple degrees from Southern Illinois University and became a home economics teacher. She taught in schools as well as in a jail, a juvenile detention center, and a homeless shelter. She is the co-author of Education Has No Color: The Story of Thelma Mothershed Wair, One of the Little Rock Nine.

- Terrence Roberts has a Master’s Degree in Social Welfare and a PhD in Psychology. He is the author of Lessons From Little Rock and Simple, Not Easy.

You can read more about their experiences and Central High and their post-high school lives at this National Park Service article.

There are a gazillion videos and articles about the Little Rock Nine online, but I used these in particular:

National Women’s History Museum

This honestly made me cry, in the best way possible. So impressed by the courage of these young people and Daisy Bates. Thank you for giving info on what happened to the Little Rock Nine afterwards. It’s so easy for civil rights activists of that era to get frozen in literal black and white in society’s mind and for people to forget that they went on to live lives of great impact and how many of them are still with us.

This is a great article. I loved learning about Daisy and the Little Rock Nine. Please review the use of the word “segregate” since I believe it is being used incorrectly in at lease one place. “Daisy, then president of the NAACP, became the leader and coordinator of the effort to segregate Arkansas schools…” I think this should say “desegregate” the schools in Arkansas, not “segregate” them. Thank you.

WOW did I miss that one in edits. Thank you. I think my brain filled in the right word for me? Egads. Thanks!

Thank you, Carrie, for this piece. While I’d known of the Little Rock Nine, I didn’t know them as individuals nor did I know Daisy Bates.

Thank you, Carrie, for shining a light on Daisy Bates and the Little Rock 9. The sad thing is the people who want to erase this history, and keep today’s students from learning about them.

This is something not taught in public school–my kids didn’t learn about it–and it wasn’t fully taught in my desegregation seminar class in college. Thank you for teaching us about Daisy Bates and her role advocating for the Little Rock Nine.

My school district was one of the last to go through court-ordered desegregation when I was in middle school, so it is a subject I’ve always been interested in. As a child, we only heard what our parents said, and that wasn’t educational. Nor accurate.

Remarkable people. It’s heartening that they went on to do so many amazing things. Thanks for sharing.

Wonder how many of their books are now available in Arkansas schools?

I first saw that photo of Eckford when I was about her age. That’s still one of the bravest things I’ve ever seen.