I don’t know why, but I am a total sucker for books about Arctic and Antarctic exploration. Bring me your frostbite, your scurvy, your long marches, and, above all, bring me my warmest pajamas and a hot cup of tea and we have what I consider to be the perfect ingredients for a cosy night in.

The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration (1897ish – 1922ish) and the many efforts to locate the Northwest Passage in the Arctic are simply crammed with stoic imperialist White men who suffer terribly for what, frankly, does not strike me as terribly good reasons. Perhaps my ability to read of their sufferings with ghoulish fascination stems from the fact that none of these guys needed to be either North or South in the first place. To borrow and bend a common phrase: you live by the poorly sealed canned goods, you die by the poorly sealed canned goods*.

Of course, in the case of the Arctic, people were already living there long before any White explorers staggered upon the scene. Yu’pik and Inuit peoples were instrumental in exploratory expeditions in the Arctic and, less directly, the Antarctic. I’ve already written about Ada Blackjack, an Inupiaq woman who survived on Wrangel Island alone for eight months after the other members of her party died.

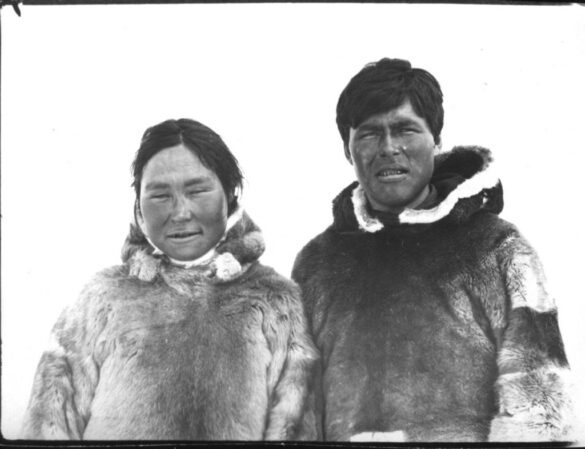

Other Indigenous women often supported expeditions, especially Arctic ones, by sewing, skinning and preserving fur and leather and cooking. Taqulittuq (also known as Tookoolito and as Hannah), an Inupiaq woman, accompanied Charles Francis Hall on many expeditions including one in which she and some crew members were marooned for months and survived because of the skills of Taqulittuq and her husband. Many other Indigenous women accompanied and supported expeditions and were never formally recognized for their valor.

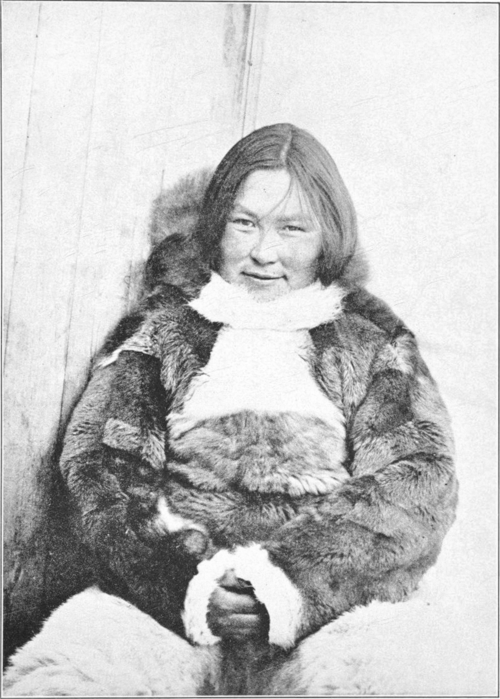

Arnarulunnguaq, the first woman to travel from Greenland to the Pacific, was born in Greenland in 1896. She related that when she was six or seven, her father, a hunter, died and the family became so desperate for food that they prepared to sacrifice Arnarulunnguaq so the the rest of the family could live, having one less mouth to feed. However, at the very last minute, her brother started crying and her mother decided not to kill Arnarulunnguaq after all. Arnarulunnguaq was (of course) powerfully changed by this experience. According to the explorer Knud Ramussen:

She says herself that the gratitude that she came to feel many years later, and the life she had almost received as a gift, has made her placid towards people.

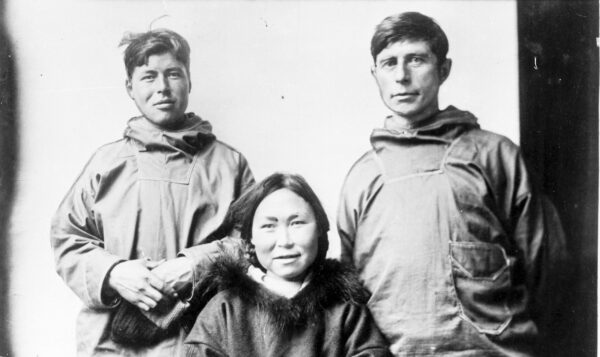

Arnarulunnguaq married a hunter named Iggiannguaq (allegedly she had a previous marriage that failed because she was “too lazy,” a trait which truly does not match the historical records of her life!). The two planned to accompany Knud Rasmussen on his Fifth Thule Expedition (1921 – 1924). This trip involved travelling from Greenland to Siberia via dogsled. Iggiannguaq died before the trip commenced, and Arnarulunnguaq asked to be allowed to continue with the trip. Her cousin, Qaavigarsuaq Miteq, filled the role of hunter.

Arnarulunnguaq cooked, built peat shelters, sewed, and maintained skins and furs as well as helping with the dogs. She drove dog sleds, gathered specimens, and assisted with archeology. She also documented the trip in drawings. Rasmussen said of her that she had:

that good humour about her that only a woman can instil [and was as] entertaining and courageous as any man when we were out on our journey.

Rasmussen hoped to use the journey to document the lives of Indigenous people of the Arctic.

Danish anthropologist Kirsten Hastrup says that because of Arnarulunnguaq’s and Qaavigarsuaq’s influence:

…what resulted was a ‘collaborative ethnography’ because “‘he Polar Eskimos were no longer being studied but studying with him, and clearly Rasmussen sees the American Inuit very much through Inughuit eyes.’

After the expedition, Rasmussen took Arnarulunnguaq and Qaavigarsuaq to New York City. Arnarulunnguaq loved riding elevators and described New York city as the coldest place she had ever been. She married Kaalipaluk Peary, son of explorer Robert Peary. Like so many other Arctic Indigenous people, she contracted tuberculosis and battled it for years. In 1925, Arnarulunnguaq returned to Thule, where she died in 1933.

*Was the Franklin Expedition of 1845 (which has nothing directly to do with Arnarulunnguaq other than being an Arctic expedition) doomed by lead seeping into their canned goods? Lead poisoning was long thought to have been one of many trials that beset the men of the expedition, but according to Smithsonian Magazine, it was probably not a factor after all. More prominent factors were starvation, hypothermia, scurvy, illness, and exhaustion.

If you like exploration stories set in cold places, I recommend the3 following, with links to those that have been reviewed on Smart Bitches:

- The Arctic Fury by Greer Macallister. A novel about Arctic exploration placing a fiction group of women as the leads.

- Ada Blackjack: A True Story of Survival in the Arctic, by Jennifer Niven. A nonfiction book about Kickass Woman Ada Blackjack.

- The Damned, a horror movie about Icelandic Fisherfolk who are being picked off one by one by a mysterious assailant while battling cold and hunger.

- The Naturalist Society by Carrie Vaughn: a novel in which a gay couple who seek funding for their next Arctic expedition becomes involved with a widow who wrote ornithology papers using her husband’s name.

- Endurance by Alfred Lansing: A nonfiction book about Ernest Shackleton and Antarctic exploration.

- The Terror by Dan Simmons. A horror novel about the Franklin Expedition. Also a television series.

- Madhouse at the End of the Earth by Julian Sancton. A nonfiction book about the first ship to overwinter in Antarctica.

Sources: