This guest post is from Lucynka! Lucynka is a long-time lurker, who has occasionally commented under a couple different names in the past. Over the last few years, she’s become really interested in the history of the romance genre, particularly those forgotten or oft-overlooked parts.

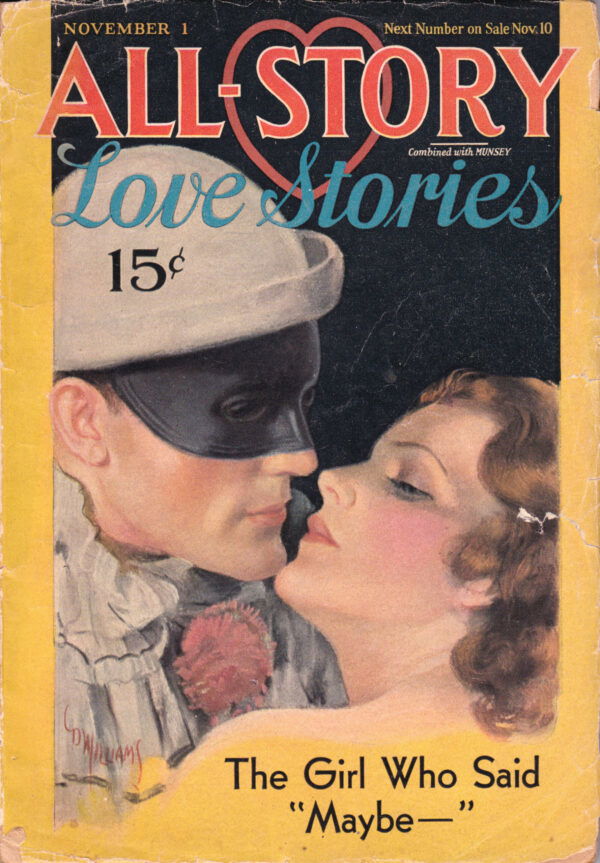

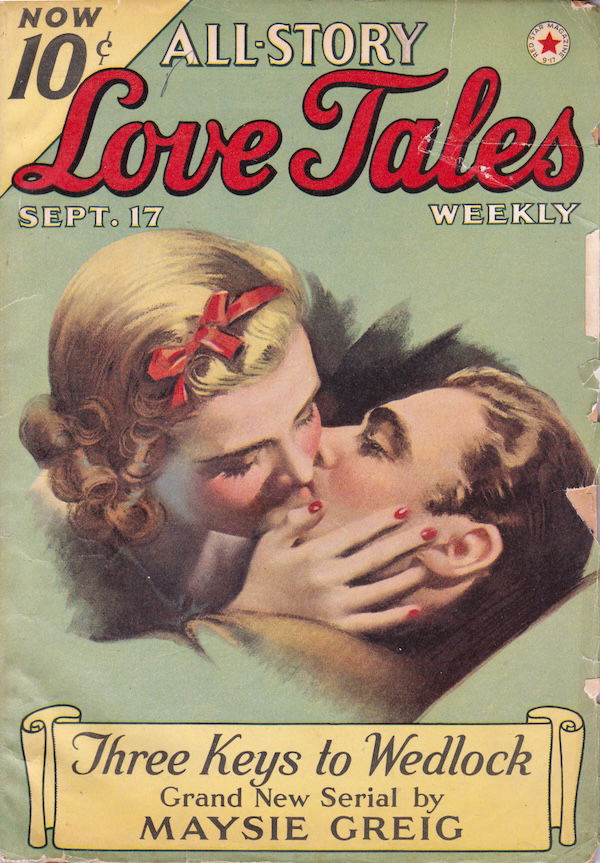

You can find her on Bluesky @lucynka.bsky.social, or else over on her WordPress, where she blogs about “obscure bullshit,” including a lot of romance pulp magazines from the 1920s-’40s – which is what she is sharing with us today! Don’t miss her reviews for The Lilac Ghost (B+) or Love’s Magic Spell (F)– and definitely don’t miss her anthology, The Best of All-Story Love: 1929, on sale and discounted right now!

…

I discovered the romance pulps (or “love pulps,” as they were also called) in 2021, quite by accident—really what I was trying to do was to hunt down some lesser-known Cornell Woolrich stories. (Woolrich was a big mystery/noir author in the 1940s, and I would also categorize him as a great, unsung, proto-feminist author—and I’ll just leave it there, lest I turn this into The Cornell Woolrich Appreciation Hour.)

The problem with Woolrich is that a lot of his shorter works are out-of-print and hard to find. But I knew he got his start in the detective pulps of the 1930s, and so—figuring there might be an enthusiast community that had digitized at least some of these magazines—I started delving into pulpdom. And while I did indeed find some Woolrich, I also discovered that the pulps (the classic pulps, that is, not the mid-century paperbacks that often get lumped in with them) were a lot more than just the detectives and sci-fi and fantasy that modern pop culture had led me to believe they were. Truly, there was something for everyone here—airplane pulps and railroad pulps and, yes, romance pulps.

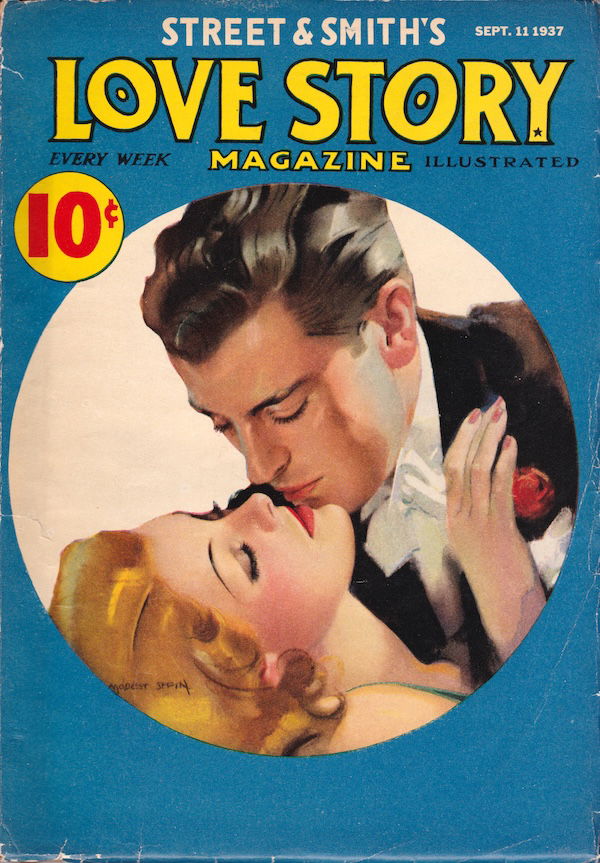

One of the resources I’d come across in my search was The Pulp Magazines Project, and I saw that they had three digitized issues of Love Story Magazine available on their site, all from the mid-1930s. I knew nothing about the romance pulps at this point, let alone anything about that specific title, but I’d had an interest in the history and evolution of the genre for a number of years, and so, curious as to what a “vintage pulp romance” might be like, I gave them a look.

I can’t remember exactly which stories I first read—mostly because they didn’t leave much of an impression, to be honest. A big problem is that I had no frame of reference for what I was reading. There were no convenient Goodreads reviews for these stories, nor even summary/teaser blurbs that might let me know what I was getting into, plot-wise.

These days, if you want to dip your toe into an old-skool bodice-ripper (for instance), you at least have the back of the book, and there are resources out there that can help you contextualize the sexual politics on display in those stories. There are authors and texts from the era held up as critically important to the genre, that can give you an idea as to where to start and what to appreciate.

With the pulps, I had none of that. In case you couldn’t guess, the pulp community is overwhelmingly male, and so there historically has been very little interest in the female-aimed romance pulps, even though they were a huge part of the industry. No anthologies or collections of popular authors, or reprint facsimiles of magazines as a whole—nothing to act as a guide. So was my initial lackluster response to these stories simply a result of them not being very good on an objective level, or was the fault my own, for not having the contextual knowledge to parse what I was looking at? I just didn’t know.

But there were, at least, elements and tropes I recognized—fake dating, marriages of convenience, etc.—and those, combined with the historical details (all of these were written as contemporaries, but due to the sheer passage of time, they now read like historicals), kept me casually poking at the issues over the course of a few days.

And then I got to “The Love Pawn” by Hortense McRaven (Love Story, March 10, 1934), which is an absolutely bonkers kidnap/heist/revenge romance, with gender politics that—if you can believe it—actually hold up surprisingly well to modern reading. I hesitate to call the story “good,” in the traditional sense of the word, but I was nevertheless riveted, and by the end of it was just like, “OH. OH, MAYBE THERE’S SOMETHING HERE FOR ME, AFTER ALL???”

A browse of the secondhand market on eBay brought up one more McRaven story (this time in the March 27, 1937 issue of All-Story Love), and thus my first romance pulp was purchased.

That said, it took me about another year before I started to become a capital C “Collector.”

As was the case with many of us, I’m sure, the pandemic saw me looking for more podcasts to listen to, and so I started to dig back into the SBTB archive, unearthing—among other things—Sarah’s 2018 interview with then-Bowling Green Pop Culture Archivist Steve Ammidown. That, combined with other interviews I found with rare book dealer Rebecca Romney, promoting her 2021 survey The Romance Novel In English, made me start thinking differently about my own collecting habits (effectively non-existent at this point), and I also started to think differently about the romance pulps as a whole—this very much forgotten part of the genre’s history.

No longer content to just passively consume whatever few, random issues were digitally available on the internet, I started to actively seek out hard copies to explore. And, well, here we are.

One of the things that continually fascinates me about the romance pulps is how very much of the modern genre’s—and specifically the modern American side of the genre’s—DNA I can see in them. Romances certainly existed before Love Story’s game-changing debut in 1921, but—in the pulps, at least—they existed in the general fiction magazines, alongside men’s adventure stories and whatnot, and that definitely influenced their tone and tenor.

A good example of this is Edwina Levin’s Honor, which I collected earlier this year. Published in 1921 in a general fiction mag, it’s emphatically a romance, but the protagonist is male, and—as he’s a gentleman thief—a lot of emphasis is put on his criminal exploits.

You could certainly make the case that the birth of the romance-specific pulps in the 1920s ghettoized the genre (you seem to get far fewer men writing romances once they become confined to dedicated “women’s” magazines), but you also see a veritable explosion of female writers, and the modern formula as we know it really starts to coalesce. Things are admittedly wobbly in those first few years (I’ve run into male-centric mysteries where the romance is reduced to a mere subplot, in addition to female-centric stories that don’t end happily), but by the late-1920s or so, it all begins to click: The HEA becomes editorial law, not up for negotiation, and (with very few exceptions) it’s female protagonists or GTFO.

Starting in the late-1920s, but really taking off in the early-’30s, you also see this seismic shift in the romance pulps, where all of a sudden (relatively speaking) everything becomes significantly less old-fashioned, less Victorian/Edwardian, and more recognizably modern—from sheer narrative style down to the sensibilities on display. This is something that was even noted in a few trade journal articles of the time (the “new” love pulp, as the phenomenon was dubbed), so, like, it isn’t just my imagination—something happened.

In many ways I feel it parallels the shifts that romance would see in the 1970s (with second-wave feminism and the advent of sex-on-page), or even the 1990s (with third-wave feminism and the genre finally moving out of the bodice-ripper era). In which case, maybe first-wave feminism is to blame for this earlier shift in the pulps—just something in the socio-political water, as it were. But I’ve also considered that it might—at least partly—be due to American authors finally finding their own voices and breaking free of the previously-dominant British tradition.

This is one of the reasons I felt it was so important to include “The Love Master” by British author Ethel M. Dell in my anthology, The Best of All-Story Love: 1929. To tell the truth, I don’t much like the story, on a personal level. (It’s technically well-written, sure, but I find the heroine annoying more often than not, and I really don’t like the messaging, that basically sees said heroine punished for her modernity with sexual assault.)

Still, Dell was a big name author at the time (notably influential on Georgette Heyer), the story is one of her extremely rare ones (never collected, as far as I can tell), and it furthermore so neatly demonstrates the differences that existed between the British and American “schools” at the time. You compare “The Love Master” to any of the other stories in the anthology, and there almost is no comparison. Which isn’t to denigrate it, but to point out that it’s apples and oranges here, not apples and apples.

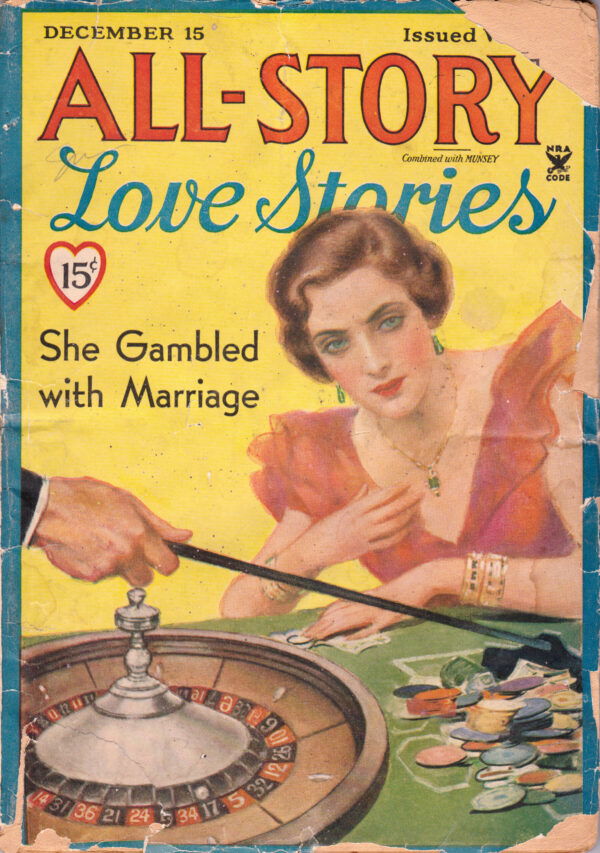

Then there’s the fact that the pulps really do strike me as the spiritual ancestor of the modern category romance, in that there were very strict word limits, and each magazine had its own specific “flavor” when it came to heat levels and the types of stories it preferred. (Love Story, for instance, tended to be very sexually conservative, whereas All-Story Love would eventually distinguish itself as a magazine more willing to be suggestive, at least, of sex/sexuality.) Readers could sign up for subscriptions if they chose, and there was even a publishing war of sorts at the time, that very much parallels the Romance Wars of the 1980s.

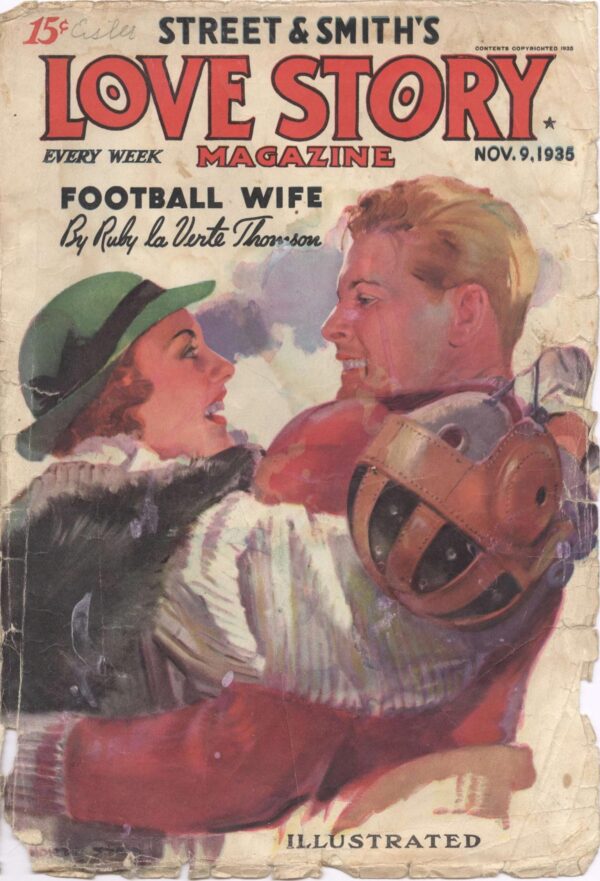

The modern subgenres as we know them didn’t yet exist (with the exception of Western romances), but I’ve nevertheless come across stories that function as prototypes or early examples of things we would now find ubiquitous: I’ve come across celebrity romances, sports romances, stories that would now qualify as romantic suspense. World War II would usher in a whole slew of military heroes, and I’ve even come across stories that I feel are best described as proto-erotica, due to the taboos they brush up against (“priests” and “sex with your boyfriend’s hot dad,” for those who are curious). So much of modern American romance as we know it is here, waiting, for anyone who’s willing to take a look.

I’ve already mentioned that “The Love Master” isn’t a personal favorite—but as far as what are some personal favorites, well, for starters, there’s “Saturday Night and No Date” by Dorothy Dayton and “The Timid Vamp” by Chet Johnson (both of which are conveniently available to read for free, via the ebook sample). “Saturday Night” starts with the small-town heroine lamenting about how a bombshell New Yorker has swept in and stolen her boyfriend. The narrative gets turned on its head, though, when the “other woman” doesn’t get demonized, but instead is apologetic and becomes fast friends with the heroine—and together they hatch a scheme to drive her boyfriend back to her. It backfires of course, but in the best way, and the author even gets some nice digs in at the double standards of the time.

“The Timid Vamp,” on the other hand, is basically a comedic enemies-to-lovers tale, between a female reporter and a hot-shot aviator—she’s tasked with kissing him for a newspaper stunt, but he doesn’t take it so well, and it kick-starts a rivalry between them. It’s funny, and sexy, and I can’t even be bothered when the hero says the heroine deserves a good spanking, because I 100% believe that—if he ever dared to try it—she would immediately turn around, haul him over her lap, and return the favor.Beyond that, there’s “New Year and New Love” by Jane Littell, who’s an important figure in pulpdom—she would go on to become an extremely popular romance author, and even a romance editor in the late ’30s and early ’40s. She was also queer, and was in a life-long relationship with another woman. Censorship practices of the time meant she was stuck writing het romance, but close readings of her work reveal some really interesting things: For instance, she wrote a fair number of misfit characters, or else—as is the case with “New Year”—her heroines were often mistaken for somebody they weren’t, or otherwise had to pretend to be something they weren’t.

Then there’s “The Tag-Along Girl” by Helen Ahern, which hits a number of the same beats as “Saturday Night and No Date,” but it’s significantly longer, and here the heroine has to balance her desire for love with her desire for a career as a professional dancer. Romance has always been reflective of pop culture, and while today you might see pop stars or reality show contestants, in the pulp era you had heroines dreaming of the stage or working in the nascent film industry (see again “New Year and New Love,” in which the heroine is a Hollywood extra).

Beulah Poynter’s “Remembered Rapture,” one of the two novellas, is yet another favorite, with a heroine who gets a job as a lady’s companion on a European trip, and gets tangled up in intrigue. Poynter was very feministic and progressive for her era, and while that’s not as overt here as it is in some of her other work, “Rapture” is still a really fun and well-crafted story, with a strong mystery element (which is the other genre she specialized in). It also has the great line, “How many bogus lords are there knocking about Europe?”—which, like, reading modern historical romances, amirite???

Lastly, I feel the other novella, “Wooing Wings” by Clelia S. Mount (a suspected pseudonym of C.S. Montanye), should get an honorable mention, if only because it features a scene between the two leads that—if you know how to read the coded language of the era—could very easily be interpreted as an interlude of premarital sex.

Honestly, they’re all favorites in their own ways. Even “The Love Master” has aspects I enjoy.

As similar as these stories can be to modern ones, though, there definitely are differences. First and foremost, they’re all short fiction—short stories and the two aforementioned novellas. Longer, novel-length serials certainly existed (and if you find an American romance novel from the period, there’s a solid chance it was first serialized in a pulp), but they definitely didn’t make up the bulk of these magazines. As such, you have to go in with short fiction expectations (which is admittedly one of the things that tripped me up at the beginning).

The storytelling tends to be a lot faster and more focused, and if these relationships get established in what seems like an unreasonably short amount of time, you have to understand that that’s a feature, not a bug. (On the bright side, it does mean you can get through a complete story in half an hour or less, so if you’re pressed for time or your brain is unable to mentally commit to something longer, these are great little ways for you to get your romance fix.)

Also, just like these stories are hetero, hetero, hetero, they’re also—in case you couldn’t guess—white, white, white. That said, “In the Eyes of the World” and “Remembered Rapture” have unusually positive portrayals of Italians, and “Wooing Wings” features a Native American side-character. (Also, in the interest of preservation, I didn’t change any of the wording, so heads up that there are some instances of offensive language, such as the g-slur being used instead of “Romani.”) As far as gender politics go, I’ve avoided the worst of what you could find, but it was a different time, as they say, and things haven’t always aged perfectly in that regard.

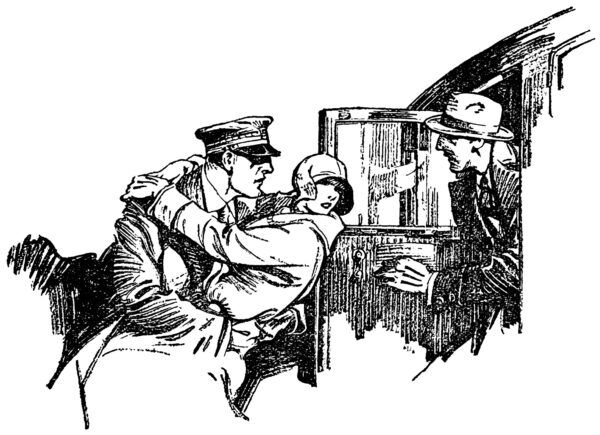

Oh, and did I mention there are illustrations? Because there are! There were illustrations in the original magazines (usually two or three per story), and I’ve gone through the trouble of including them here!

If you’re curious about pulp romance, without tooting my own horn, I would recommend The Best of All-Story Love: 1929, as it’s the first anthology of its kind out there. (I’ve collected some other stories that are now in the public domain, but most of those so far are mysteries with romantic subplots, not strict romances.)

I would also highly recommend Laurie Powers’ 2019 book Queen of the Pulps, which is a biography of Love Story’s long-standing editor, Daisy Bacon, and—to date—the only formal text on the subject. (While it is indeed a biography at its heart, it also functions quite well as a history and overview of the romance pulps, and even the pulp industry as a whole.)

Aside from that, there are a decent amount of magazines that have been scanned and uploaded in full to Archive.org (most of them are issues of Love Story, including the three I first found through The Pulp Magazines Project). Some of them—along with other stories from my personal collection—I’ve taken to cataloguing on my blog, with summaries, content warnings (both trope and trigger), and story links, so you’re welcome to browse to see if something catches your fancy. (If I can save someone from aimlessly floundering like I did at the beginning, so much the better!)

…

Have you read pulp romance stories before? If you’re curious, Lucynka’s book, The Best of All-Story Love: 1929 is available now on sale for $5.99 through February 15, 2026. Thank you for the guest post and thorough history of romance pulps, Lucynka. This was fascinating.