There are a lot of ways to qualify as a kickass woman and although Vera Brittain, a pacifist, did not literally kick any asses, she figuratively kicked a hell of a lot of them in many, many ways.

The ass-kicking began when she insisted on getting an education against the wishes of her parents and it continued with her grueling work as a nurse in WWI. After the war, Vera became a writer, journalist, and political activist.

The ass-kicking began when she insisted on getting an education against the wishes of her parents and it continued with her grueling work as a nurse in WWI. After the war, Vera became a writer, journalist, and political activist.

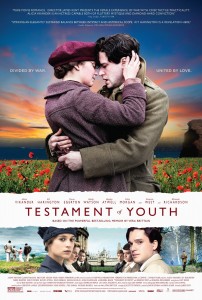

She worked for the pacifist cause and wrote several memoirs. Her most famous memoir, Testament of Youth, had a huge influence on how people thought about WWI. It’s recently been made into a movie, reviewed by Redheadedgirl.

Vera was born in 1893 to a solid and conventional middle class family. She was determined to go to university, like her brother, and she won a scholarship to Somerville College, Oxford, in 1914. Her father felt that higher education was unnecessary for women, but Vera’s brother, Edward, and his visiting friend, Roland, backed Vera up and she won her father’s consent. Vera was close to Roland and Edward, as well as two of Edward’s friends, Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow.

When WWI broke out, Edward and Roland enlisted. Roland and Vera became engaged while he was on leave, in 1915, and Vera dropped out of Somerville to become a Voluntary Aid Detachment Nurse. She was working in a hospital in London when she learned that Roland had been killed.

Vera was, initially, thrilled with nursing, but she was increasing worn down by the difficult conditions and heart-broken by her cases, as she described in her diary:

“Sometimes in the middle of the night we have to turn people out of bed and make them sleep on the floor to make room for the more seriously ill ones who have come down from the line. We have heaps of gassed cases at present: there are 10 in this ward alone. I wish those people who write so glibly about this being a holy war, and the orators who talk so much about going on no matter how long the war lasts and what it may mean, could see a case – to say nothing of 10 cases of mustard gas in its early stages – could see the poor things all burnt and blistered all over with great suppurating blisters, with blind eyes – sometimes temporally, some times permanently – all sticky and stuck together, and always fighting for breath, their voices a whisper, saying their throats are closing and they know they are going to choke.”

Vera was posted to Malta in 1916 and to France in 1917. In France, she worked with mustard gas victims in a hospital that was frequently bombed. Most of her patients in France were German prisoners. In 1918, Vera’s father demanded that she come home and take care of the household after Victor and Geoffrey were killed and her mother had a nervous breakdown. Edward was fatally shot by a sniper soon after.

After the Armistice, Vera returned to Somerville and switched her field of study to history:

I never regretted the decision, for in studying international relations, and the great diplomatic agreements of the nineteenth century, I discovered that human nature does change, does learn to hate oppression, to deprecate the spirit of revenge, to be revolted by acts of cruelty, and at last to embody these changes of heart.”

She added that she hoped that studying history would help her “understand how the whole calamity (of the war) had happened, to know why it had been possible for me and my contemporaries, through our own ignorance and others’ ingenuity, to be used, hypnotized and slaughtered.”

During this time, Vera met Winifred Holtby, who was to be her life-long friend. After graduation, the women became roommates in London where they both worked as journalists and novelists. Vera married George Edward Catlin in 1925 and Winifred moved in with them. There were always rumors that the two women were lovers, but Vera always presented their relationship as a platonic one, including in her memoir about Winifred (Testament of Friendship). Vera’s daughter has been quoted as saying that Vera felt rumors devalued female friendship:

Some critics and commentators have suggested that their relationship must have been a lesbian one. My mother deeply resented this. She felt that it was inspired by a subtle anti-feminism to the effect that women could never be real friends unless there was a sexual motivation, while the friendships of men had been celebrated in literature from classical times. My mother was instinctively heterosexual. But as a famous woman author holding progressive opinions, she became an icon to feminists and in particular to lesbian feminists.

Whether their friendship was physical or platonic, it was absolutely central to Vera’s life. Her husband, George, resented the relationship, feeling that she put Winfred first. He also struggled with Vera’s deep and lasting attachment to Roland. She spent very little actual time with Roland during his life and most of their courtship occurred by letter, so it was easy for Vera to idealize him. In many ways, Vera never left WWI – it continued to dominate her life. But she was able to use her experiences and losses as a motivation and fuel towards preventing such losses for further generations through her work as a pacifist.

It took Vera seventeen years to write Testament of Youth. Originally she wanted it to be a novel but she couldn’t get the voice right. Eventually she developed the confidence to write it as a memoir, and it was an instant best seller.

Other books were more controversial, including Humiliation With Honor, a book about pacifism that was written in 1943, and Seeds of Chaos, an indictment of area bombing. She faced huge amounts of criticism in WWII for being unpatriotic, but regained some public sympathy when it was discovered that her name was on a list (taken from the Gestapo) of people to be immediately arrested should Germany succeed in invading and occupying Britain.Vera was a life long supporter of the Peace Pledge Union and, later in her life, was active in protesting against nuclear weapons. Vera was a “practical pacifist” who believed that during a war it was her duty to relieve human suffering through activities such as nursing, working with hunger relief, and aiding refugees.

There are scores of resources about Vera, including her own writings. The website I found most useful for this post was Spartacus Educational (http://spartacus-educational.com/Jbrittain.htm). It has tons of info on Vera plus links to pages about most of the important people in her life.

When I read Testament of Youth it knocked me over — not just the account of the devastation that the war wreaked on Vera (and her slow recovery in the last part is equally compelling), but her observations of how narrow the pre-war mindset had been and her growing awareness of justice and feminism. She hung out with a bunch of other early feminists and intellectual women — Rebecca West is the only other name I remember at the moment.

An amazing but tragic life. Thanks for telling us about her, Carrie.

You don’t mention the other resources: the wonderful Letters from a Lost Generation and Beryy/Bostridge’s Vera Brittain biography which shows among other things that Vera exaggertaed her parents’ opposition to her getting a university education.

Thanks so much Carrie for this series. Thanks for introducing me to amazing women previously unknown to me and doing so with just the right touch -you have an entertaining way of getting across serious topics without sending the reader into snooze territory. (Hopefully, I can, in a small way, return the favour. I am a great fan of Maria Popova’s blog, Brain Pickings,. I’m forever recommending it to others and do so again in case you haven’t heard of it.)

Anyway, I hope you keep these coming. In some cases, I’ve gone on to read more, or to buy further texts, while with others your article has been enough.

Finally, this month, a woman I’d previously read about and have admired for decades., for her courageous pacifism alone. And she could write. Her attitude to female friendship wasn’t bad, either.