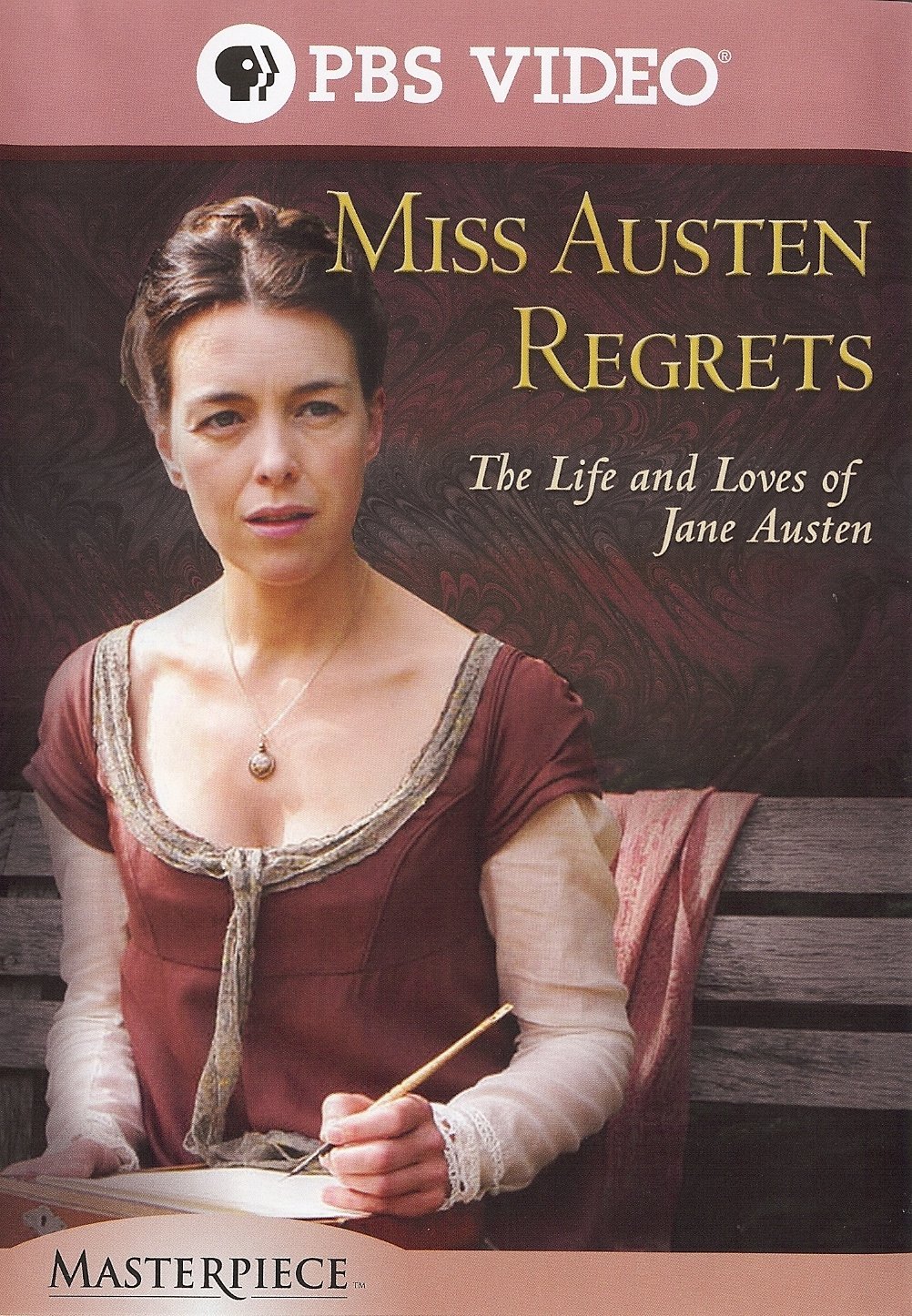

Miss Austen Regrets is a BBC movie about the last years of Jane Austen’s life. It’s beautifully cast, with wonderful dialogue, much of which comes straight from Jane Austen herself, and Olivia Williams is a fantastic Jane – very human, funny, smart, and fun loving. But the movie tries to do three things at once. It tries to show the consequences for a woman of Austen’s time being single, it tries to show Jane as a woman with a broken heart, and it tries to tell us that Jane does not “regret” being single because being single gave her freedom to write. Alas, the latter half of the film in particular is so depressed in tone that we don’t believe Jane has no regrets – we believe that she’s very sorry that she didn’t find true love, preferably with a rich guy. It’s a plausible but frustrating portrayal.

The very first thing you should know here is that Austen’s niece, Fanny, is being courted by a Mister Plumptree, and young Mister Plumptree is played by…wait for it…TOM HIDDLESTON. He’s an infant! He’s so unknown that he barely even makes the credits! Behold the adorableness of the Hiddles!

Plumptree is clearly mad for Fanny, but he’s also rather pompous (he ruefully describes himself as “an ass”). Fanny wants her aunt’s advice on whether or not to marry him. While the audience screams “MARRY HIM!” at the screen (because we know what is to come and that Hiddles will soon be so amazing that birds fall out of trees, stunned, at the mere sight of him), Aunt Jane cannot help but notice that Plumptree is opposed to fun and very, very fond of sticking his foot in his mouth. Fanny has doubts about Plumptree right up until he becomes unavailable at which point she blames her aunt for ruining everything.

Meanwhile, as the family finances deteriorate, Jane’s mother blames Jane for not marrying rich and thus subjecting the women in the family to financial hardship. One of Jane’s ex-suitors blames her for not marrying him just because he was poor at the time, another brother condescends to her, and the brother who actually likes her is sick. So basically everything is awful for Jane and it’s extra awful because Jane is blamed for making everything awful for everyone else. In ninety minutes we go from this:

to this:

So – back in the day Jane had three suitors. She liked Tom LeFroy, but her family ran him off because he had no money. She rejected Rev. Brook-Bridges (played by a very sad Hugh Bonneville) because he had no money either. She accepted an offer from the rich Harris Bigg-Wither, but a day later she turned him down because she didn’t love him. No one else came along and Jane is lonely and stressed about money. The movie’s central question is – does Jane regret turning down the men, since she knows know that she will never have true love?

My feelings about Jane Austen Regrets are confused. The acting is stellar. The first half is charming without being too cutesy. It has Olivia Williams (Dollhouse) getting drunk and gossiping at a party with her young niece, who is played by Imogene Poots. Jane says deliciously witty things and is naughty in just the perfect way that we might imagine Jane to be. Also, for a little while, we are graced with the presence of The Hiddles Himself. What’s not to like?

What’s not to like is that in the second half the movie becomes very dark (also Hiddles departs, and the sun sets in my soul), and it is revealed over and over again that Jane is lonely and bitter about it. Near the end of her life, she tells her sister Cassandra that she only regrets staying single because the consequence is that Cassandra and their mother will be poor. Other than that, she’s happy to have her freedom. But we’ve seen, again and again, Jane being haunted by her lack of a romantic love life for emotional, and not just financial, reasons. So when she says this to Cassandra, it’s difficult to believe – maybe Jane thinks it’s true, but she hasn’t acted as though it’s true.

Now, I don’t actually know how Jane felt about having been single all of her life. So much of Jane’s life is shrouded in mystery that I don’t believe anyone knows. It’s certainly plausible that she was bitter about it – but I find it rather insulting. Jane’s letters do not express much romantic longing – she was frustrated about money and ill health, and rather relived not to be having endless babies like so many of her friend. By portraying Jane’s life in such unrelentingly tragic tones, the movie reinforces the idea that women cannot be happy as single women – not simply because of the constraints of society, but because they will wither from loneliness.

The movie also presents false choices and asks us to invest in them. Jane insists that staying single made it possible to write. That would be a classic artists’ dilemma (family vs. career) but in Jane’s case, as a single woman, she had overwhelming household responsibilities. She ran the house for her mother and Cassandra, she nursed her mother through a long illness, she spent months assisting relatives and friends with their health issues and their children, she had nieces and nephews all the heck over the place – the woman was BUSY. It wasn’t until 1809 that her more routine domestic duties were lessened so that she could concentrate on writing more, and that was hardly a foregone conclusion. So the idea that she chose to be single so she could write seems unfounded. Regardless, there’s nothing that I know of to support the idea that Jane was mopey and bitter about her broken heart while her mom yelled at her all the time.

In fact, the whole idea that Jane deliberately chose to be single is dubious. Jane was quite popular as a young woman – she loved to dance and was no wallflower. But she’s only reported as having rejected one proposal in her life (from the rich boring guy). Her romance with Tom LeFroy was thwarted by both of their families (and is only hinted at in Jane’s letters so it may not have been that big a thing to start with) and the romance with the character played by Hugh Bonneville seems to be a complete fabrication.

Of course, we don’t have all of her letters (Cassandra burned many of them) and she might not have written her deepest feelings in a letter anyway – but based on what little we know of her she could have been portrayed just as reasonably as a woman who truly did have no regrets.

This movie is worth seeing for the performances, all of which are stellar, the dialogue, which is often brilliant, and of course the clothes, because some of us never, ever get tired of those clothes. Bonus points to the costume department for having Jane wear several low, undramatic turbans during the course of the film. My understanding is that this kind of turban or wrap was quite common at the time, but most productions stick to hats and bonnets. Overall the film is shot in a lovely way – the scene in which Fanny runs through a hedge maze leaving a red ribbon trail behind her for Plumptree to chase is a not at ALL metaphorical fashion (cough*SEX*cough).

Ultimately, the problem with the movie is that it tells us that Jane is happy with her choice to focus on her art while relentlessly showing that she is utterly miserable (especially once Fanny becomes angry with her and the family finances worsen). I believe this is a problem with writing and direction, not acting – Olivia Williams commits to the part completely. The scene where she and Fanny get drunk and spy on the guys at a party is one of the most lovely and hilarious moments in cinema. She’s the cool aunt we all wish we had.

But the movie can’t make up its mind how it feels about her choices and it settles for telling us something uplifting while showing something depressing. We’ve already been told so many times that women can’t be happy without romantic love. It’s a legitimate story but one we’ve been told so often that it falls into cliché. I regret that this movie fails to seize the opportunity to make a different choice in portraying Jane’s attitude towards her life.

A clarification: when I say “It’s a legitimate story” , I don’t mean “It’s legitimate to say that all women are unhappy without romance.” I mean, “One could legitimately tell a story in which a specific woman is unhappy about romance.” Upon re-reading, I realized that my wording was sloppy!

Interesting review of an interesting-and-flawed-sounding movie! Your excellent points about the movie kind of waffling between “it’s great to not marry” and “it’s tragic to not marry” seem to me to point to a fundamental deep-culture feeling we’re still dragging around with us, that a good life for a woman still, if we’re honest about our secret beliefs, necessarily involves marriage: that it is in fact always a failure or even a tragedy if a woman fails to marry, like… what has gone wrong? How can we figure out where she erred???

Which is hard to reconcile with the lives of female geniuses and great artists. For a good time, whenever you read about a great female artist or writer or scientist/etc of days gone by, always scroll down the “personal life” part of her Wikipedia article and check if she married and had a mainstream domestic life with children. Very, very often, the answer is a firm NO. It’s hard to say, of course, how many of these women might have married if the perfect fellow had come along and asked, and how many intentionally remained single so they could do their work. I recently read about the idea of “the best, or none” among New England early feminists in the 19th century, many of whom had plenty of offers but felt that unless they could have the type of marriage that was a meeting of souls, they were not interested. And it seems semi-plausible to me that female geniuses of days gone by might have had unusually strong feelings along these lines, and been less willing to settle?

The historian Amanda Vickery talks about how, in the Georgian and late-Georgian periods, about a third (!!!!) of ladies of “good family” (aristocracy down to landed gentry, basically almost all of the women we read about in our questionable historical romance novels) would never marry. Because of primogeniture, the way wealth was divided, and cultural ideas about how okay it was to work for money, there were never enough wealthy sons of good family to go around as husbands. So huge numbers of women who had been raised to marry simply could not do so. Not marrying in those days, for a man, seems like it was not necessarily grim or perceived as a failure (although Vickery also discusses how we may be wrong to apply contemporary ideas of swinging bachelorhood to Georgian bachelors, who, in her read of the time, might have felt permanently excluded from what “true adult manhood” was felt to be at the time.) but I think it’s fair to say that for women, it was more complicated.

I’m sure some of them were happy to not marry, probably the ones who had some money and so some freedom. But doesn’t it also seem likely that many of them were effectively trapped in the households of fathers (and then brothers, or even nephews) as kinda-unwanted hangers-on, free domestic labor, etc, and didn’t like it?

Vickery quotes from a diary kept by a spinster daughter of nobility, I think, maybe an earl’s daughter? Who never married, and lives in her brother’s household. The lady in question seems keenly conscious of the crummy aspects of her life – not having her own home and space, not being really an adult in the household, but a hanger-on, being treated as unwelcome or a freeloader, being terribly lonely and unfulfilled, not having honest/close relationships besides her cat. Pretty grim.

Hearing this “one third of ladies never married” statistic REALLY reframed Pride and Prejudice and the respective decisions of Elizabeth and Charlotte for me. Elizabeth’s refusal of Mr. Collins seemed almost foolhardy after hearing this, and Charlotte’s acceptance of him seemed much more sensible and comprehensible. Still awful, but… I understood in a new way why it would be a practical decision for her that might be a better option that remaining unmarried.

But it also makes a person think that the movie’s take on Austen’s romance regret is kind of wrong. Like, she writes this book that is entirely about whether a woman – even two women in difficult circumstances like Lizzie and Charlotte, neither of whom is a great heiress or otherwise likely to marry well – ought to jump at marriage if it isn’t a meeting of minds? And it seems to me that the book argues “no”, argues “the best, or none”: Charlotte’s choice to marry a buffoon is understood compassionately, but seen very clearly as one that is full of discomfort, that extracts a price. Elizabeth rejects a super-rich non-buffoon who is in love with her because she thinks he’s rude, and the book doesn’t think she’s an idiot for doing so, I think. There’s also that part that always struck me, when Elizabeth is visiting Charlotte, and she meets Darcy’s cousin, Fitzwilliam, and they have what seems to me to be a clear flirtation between two people who could probably happy marry each other if circumstances were different. Then Fitzwilliam casually drops the info that he needs to marry for money. And the book just sort of accepts it as a given. It isn’t a huge tragedy or something Elizabeth rails against, is it? It’s just – well, he’s not available because the realities of life are what they are.

(That doesn’t really have anything to do with anything, but since I was already writing a dissertation, I left it in.)

I don’t have much to contribute to the substance of this review–although I do find myself thinking of the mystery series by Stephanie Barron, in which Jane was the heroine. I never did finish those, and part and parcel of that was how they were getting pretty close in the timeline to where Austen actually died in real life and I wasn’t at all sure I wanted to go there.

All that said, though: OMG lookit the blond curls on baby Hiddles. He’s adorable!

@Janet – I specify in the review that her duties were significantly lessened so that she could write more when the family moved to Chawton in 1809

My take on the movie was that she was upset about lack of money and aging and illness. Not that she hadn’t married. That she couldn’t care for her family through the money made on her writing. It is her mother and brothers who go on about her not marrying.

One of my favorite words is “bittersweet”. If asked for a word to describe her actual life, it would be that.